In some parts of the southwest, stating the fact that a not-insignificant portion of cowboys were and are and continue to be queer (which could be, depending on who you ask, an overwhelming majority) is tantamount to pissing on the Bible.

Selling sex is nothing new. It always amuses me when people act like overt sexuality is some fresh morphology of the modern age. There’s Mesopotamian art and poetry out there that could strip the paint off a barn.

But these days, we’ve been sold a sterilized sex made plastic by the money it stands to make. Adsense as aphrodisiac, it’s very essence is mutable—your every strangest desire is searchable, reachable, almost-so-close-to-fuckable—but it doesn’t yearn.

Where is the sex that yearns?

I’ve found it of late in, place of all places, Westerns.

The one-two punch of Annie Proulx and Ang Lee are the easiest sources to point to for the simple fact that gay cowboys winning Oscars deserves to hold a sticking point in the cultural memory box. But the road was driven years beforehand, in both fiction and fact, and its furroughs continue to deepen today.

Of course the past could never really be so overt as it was able to be in 2005 (even then, let’s be honest: the waters have only slightly calmed for our barges in the cosmic sense—and seem to be growing ever choppier). But the one that got it right first, in my expert* opinion, is For a Few Dollars More.

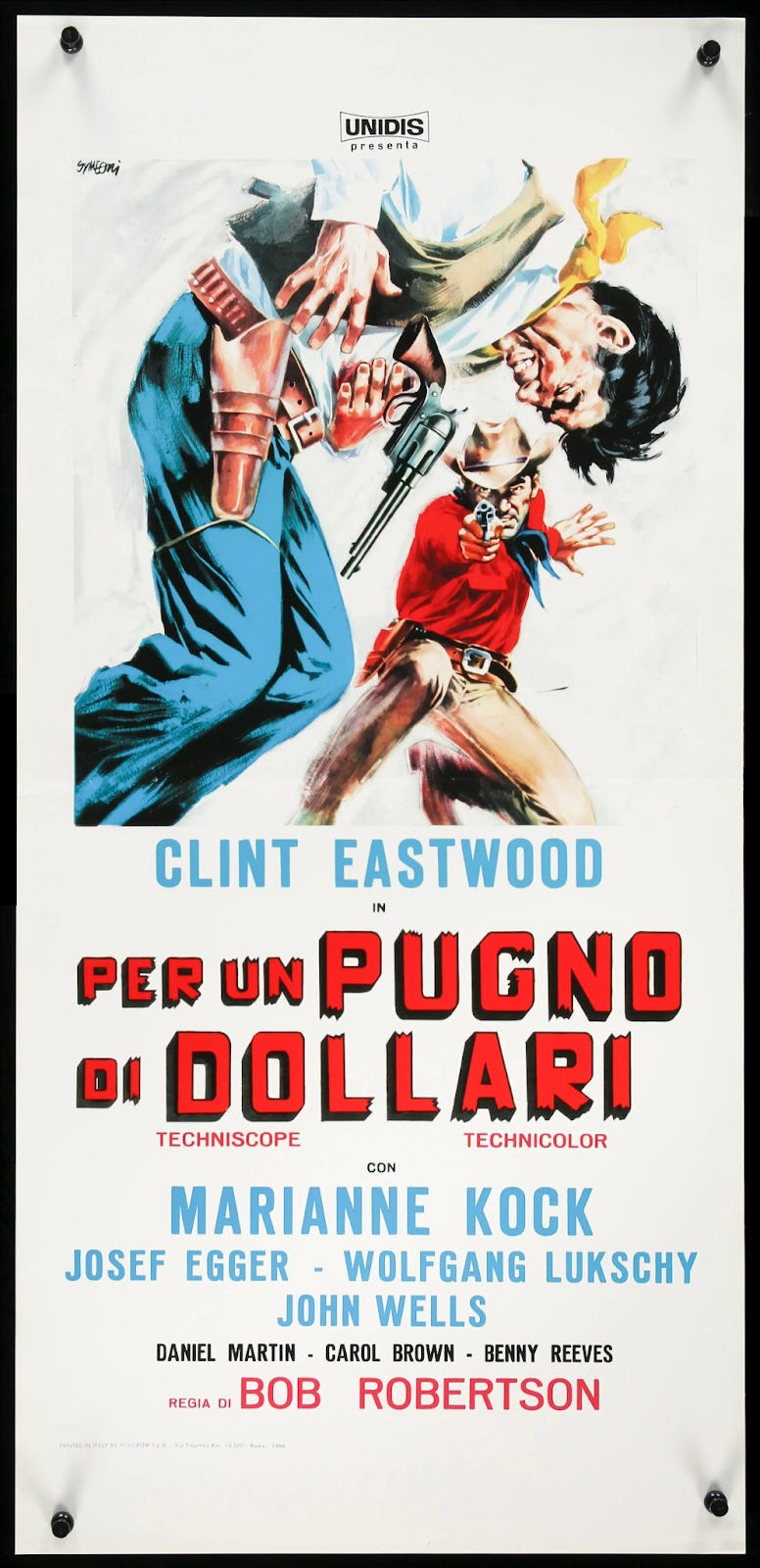

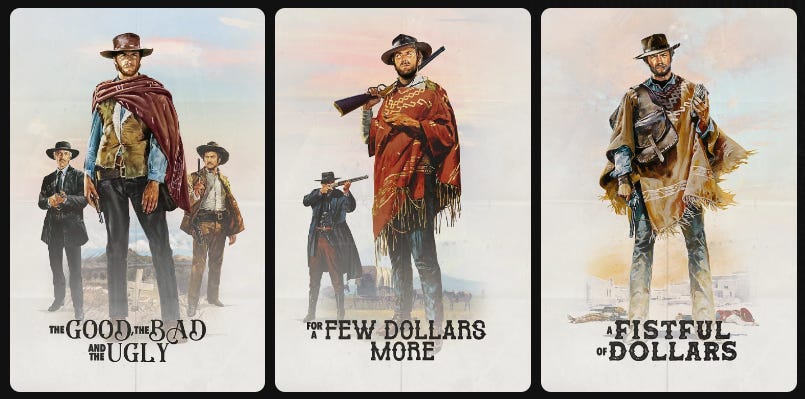

Shot in Almería in the mid-1960s, the Dollars trilogy found its locations in Hoyo de Manzanares, the Cabo de Gata-Níjar Park, and the Tabernas Desert. These locations smack appropriately of cinematic legend (and are still a pilgrimage for modern filmmakers—serendipitous references to Brokeback included at no additional cost). For the uninitiated, we have three films that blew the lid off the Spaghetti Western genre with the white-hot speed of something gaining entry into atmosphere: Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

The stories of these three films are connected with fine threads of their own mythology. Eastwood’s character, the Man with No Name, is known only by what others call him in each of the three films: Joe, Manco, and Blondie. Three persons in one cowboy—but the Jesus allegories mostly stop there, not especially considering his morals are so deliciously gray for this grimacing turncoat of an antihero. The timeline between each film exists because Eastwood looked great in a poncho, and his costumes didn’t change very much across all three films.

Usually, Westerns have one thing we all expect from the wild west with its laissez-faire make-your-money-how-you-make-it attitude: brothels and tits. For most Westerns, sex workers provide a Circe’s island sort of stopover for our heroes on their way across the ocean following their bandoliered Odysseus. They go to the cathouse, we get a tidy Hays Code fade-to-black while the music swells, and then we inevitably come back up on a scene of our hero tugging his suspenders back on or even having a shave in the aftermath. The gal has taken the time to put her lingerie right back on and lounge on the unmade bed, where she dispenses her wisdom about whatever is most convenient to the plot—who’s who with bank guard rotations, a corrupt governor, even a red herring or two if the script loves women enough to make them smart.

Occasionally, this Sybil-with-a-garter-belt trope is even subverted. In Man of the West (1958), we have the lovelorn Billie—shown above, who serves ultimately as a sort of golden calf ideal to the hero Link’s unbreakable orbit around his old outlaw life—put upon by a group of bandits to give them a striptease until one of them stops it with the last vestiges of his humility. Nobody shaves or waxes poetic in the daylight afterward, although we do get a particularly tender discussion in the runoff of this one about how Link misses his wife.

But For a Few Dollars More is even more unique. There are only two women we ever see on screen, and neither of them have any real lines. In fact, the women could just be cardboard standees of themselves and achieve the same presence.

One of them is essentially in bio-drag, played for a bit—an inn owner, a very small man, talks a mile a minute and stands on a box while his trireme of a wife simply bats her lashes and looks pretty while towering over the rest of them. The other is (spoiler alert for a film almost 60 years old) Colonel Mortimer’s sister, his raison d’etre, who is raped by the villain El Indio and shoots herself dead in the middle of it. She says nothing that isn’t a scream begging for her life.

So, in cruder terms, we get meat puppets. Given the time period, both diegetic and non-diegetic, it’s no surprise that it isn’t a very kind film to women. This is a genre built on the bonfire sort of machismo that results in things like shootouts and bank robberies and double-agenting, and that’s why it’s fun.

It’s also fun because the absence of women in For a Few Dollars More makes it utterly, unassailably queer entirely by accident.

Here now comes a section I would like to call “Gian Maria Volonté Knew Exactly What He Was Doing.”

Villains are usually not somebody we root for. El Indio is, on paper, a complete piece of shit. But when he does something like light his cigarette from the end of someone else’s (colloquially called ‘buttfucking,’ which is a whole other can of beans) or make plans with his second-in-command about how they’re going to run away together into the desert once all this is behind them, all I can see is a complete piece of shit who is also a flaming queen.

He has a veritable harem of henchmen. He holds court with them in a raided mission church, granting gospel like a knock-kneed Christ as the drag mother of a rambling Haus of Tucumcari. He’s obsessed with a woman he killed because he saw her fucking another man. He is assailed by dreams of terrible, rapturous things that he has done, or soon plans to do, and wakes from them smiling.

(I could get Freudian with this. I won’t. There isn’t nearly enough cocaine in my system.)

The more intriguing thing to me about For a Few Dollars More is that it isn’t just the villain who gets queer-coded in this confounding twilight of the Hays era. I don’t think this was on purpose, but guess what happens when you don’t have any women of substance in your film?

Remember what I said about brothels as waypoints in Westerns? The places they go to save their game (have a drink), replenish their health (have a quick fuck), stock up on healing items before diving in to face a big boss (shave, dress, etc etc etc)? You can’t have a dyed-in-the-wool Western without sex work.

Well then. Manco and Mortimer drink. And smoke together—see the colloquialism from earlier, the inherent symbolism, the handshake of it. And fade to black. Watching this exchange on mute is a delight of innuendo.

On top of that, say nothing of the hat-shooting scene that comes just before it as an allegory for the cruising that led them there: young buck against a more seasoned sort, Mortimer’s hat as an object of self-acceptance being kicked down the street by Manco’s toothy bullets, and on and on and on.

But despite all this, I know Leone wasn’t out to make a queer film. It’s a genre trilogy of which the second piece just happens to be very easy to interpret through this lens because he was so focused on telling a story about troubled men doing bad things. He was just telling a story about cowboys.

And there’s the rub: when you really look at the history, the queerness of cowboys and their origins becomes impossible to ignore. It seeps out through its own pores like sweat building on a brow beneath a hat band. You can’t escape it, and trying to do so would be a crying shame.

I’m not saying anything particularly fresh or groundbreaking with this. I think I mostly just wanted to talk about cowboys, just like Leone. But past the cowboy-as-masculinity, past the bravado and the leathers and the long drives, waits always the quiet journey that takes us home.

There’s a reason queer folks are drawn to these staples of Westerns, of homesteading and taking the jobs that come our way via the proverbial bounty or otherwise. Just look at the IGRA, drag rodeo, Orville Peck, the legacy of trans and genderqueer cowpokes that has been inalienable from the mythos of the Old West since its installation in American legend no matter how fiercely people always try to cover it up or muddle it away.

We make home in the places we trust to hold others like us—physical places like the desert outside of Madrid, or even more simply intangible things; stories about strangers with no name and those who cross them.

When home exists in the margins of other people’s normal, we must slip coyote-skinny through barbed wire meant to keep us out; we must lay timbers in unforgiving dirt and dig rows in ornery mud and batch indiscriminately with those who make us whole.

We work for it. We ache. We wrangle our own belonging.

I’ve been drafting something this summer that has become somewhat of a love letter to Westerns of all walks, Spaghetti or otherwise. My loftiest goal for it when it’s ready to blink in the proper light of day is that it rings with the same earnestness that made me fall in with stories like the Dollars trilogy, or Cat Ballou, or the entirety of Gary Cooper’s oeuvre. There’s no place for high-gloss polish with those stories. You get spit-shine and camp, and a hefty dose of irreverence that doubles back and becomes cracked-chest honest again—and I think that’s really the best we can ever aim for with the things we write.

Fuck perfection. I’ll take my boots with a little bit of dirt still caked to the rind. Means they’ve been walked in; lived in; maybe even loved in.

*By “expert,” I mean “uppity Sapphic living in Texas.” We take liberties with language in these parts.

~~~~~~ Book Updates ~~~~~~

SHOOT THE MOON, a midcentury story about wormholes and clinging to the time we have left with the people who love us, comes to Putnam Books in fall 2023 — stay tuned for more coming soon.

~~~~~~ Reading Recs ~~~~~~

MERCHANTS OF CULTURE by John B Thompson

I saw Allison Epstein recommend this a few weeks ago, and it’s been a very helpful guide to the guts of publishing that go on behind the scenes as I ramp into my debut year. If you have any interest in the morays of trad pub, check this one out for a thorough education.

WHY FISH DON’T EXIST by Lulu Miller

I picked this one up because I’m a slut for Radiolab, and I’m loving it so far. Anything that teases “obsession and murder” on the jacket copy is going directly onto my to-read list, and this one should absolutely make its way to yours.

~~~~~~ Currently Listening ~~~~~~

Citizen Sleeper OST — Amos Roddy

Amos Roddy’s music is some of my favorite “put your head down and get shit done” music. Ethereal and achy and just the slightest bit unhinged, this one is perfect for [gestures at current events] all of everything happening these days.

Teeth Marks — S. G. Goodman

A dear friend of mine put me onto this album, and it’s been perfect for these last several weeks of burnoff from a long and sticky summer.